WWII War Correspondent Document & Insignia Group

$5,500.00

William Strand was a war correspondent for the Chicago Tribune News Service during World War II, reporting on the war from North Africa, Italy, and Western Europe. This group is a massive and unique collection that includes Strand’s journalistic work, his wartime personal and business correspondence, and his military insignia and memorabilia.

I.Summary

The archive of war correspondent William Strand is comprised of literally thousands of pages of documents. These include hundreds of letters written during the Second World War between Strand and his wife, as well as correspondence that Strand received from friends and family members during the war and letters exchanged between Strand and his editors back at the Chicago Tribune while he was serving overseas. The archive also contains various documentary materials received from, or relating to, the American military during the war, these having been received by Strand while he was serving as a war correspondent.

More specifically, there are well over 500 separate pieces of wartime correspondence and related materials with many, if not most, of the letters running to multiple pages. Additionally, Strand, his wife, Strand’s Mother and, it seems, most of their friends, owned typewriters, and they used them. Most all of the hundreds of pieces of correspondence in the archive are typewritten and completely legible.

The materials in the archive further include a “clippings file” which contains all of the articles that Strand wrote as a reporter and correspondent for the Chicago Tribune between 1938 and 1948. There are more than 1,100 such articles and, again, the majority of them (over 600) date from the years 1941 to 1945, including the period during which Strand was serving overseas as a Tribune war correspondent.

Finally, the archive includes personal memorabilia, including 25 pieces of scarce “War Correspondent” military insignia that Strand wore during his time in Europe, as well as the actual Purple Heart decoration the Strand received after being wounded in a German aerial attack on the Anzio beachhead.

II. William C. Strand, Jr.: Biographical Sketch

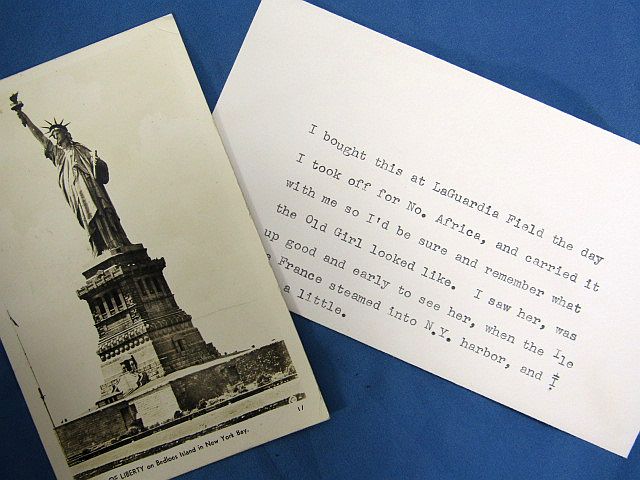

William C. Strand, Jr., was born in 1911 in Chicago. Between 1931 and 1933 he attended both Brown University and Washington University before embarking upon a career in journalism. By 1938 he was a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, covering crime and local politics. In 1940 the Tribune sent Strand to Washington to serve as a national political reporter for the Tribune News Service. With the entry of the United States into World War II, Strand became a war correspondent for the Tribune, arriving in North Africa in 1943. Strand would then cover the war in Europe as it continued, attached to the American Army as it fought in Sicily, on to Italy, and into Western Europe after the invasion of Normandy in June of 1944.

Following Strand’s return to the United States and the end of the war in 1945, he continued to write for the Tribune for three years, covering stories of both local and national interest in the post-war period and, significantly for Strand, traveling to Alaska to report on political and regional events as that U.S. territory was working its way towards statehood. Ultimately, Strand left the Tribune to remain in Alaska and to become the managing editor of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner from 1948 until 1951.

The materials in the archive make it clear that Strand had undoubtedly made a number of significant personal contacts in his days as a political reporter for the staunchly Republican Chicago Tribune and, with the election of Dwight Eisenhower as President in 1952, Strand entered government service. In 1953 he became the Director of the Office of Territories within the United States Department of the Interior, a position which placed him in charge of various government projects and operations in the American territories, including his former home of Alaska. After two years Strand became Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, Frederick Seaton, and Strand also served as the Department’s Director of Information from 1955 to 1958. Thereafter Strand became the Director of Public Relations for the Republican National Committee, a position that he held until he returned to the field of journalism as a member of the editorial committee of the Chicago Sun Times.

II. The Archive

The Strand Archive is only partially organized in its present state and much of it remains unsorted. Virtually all of it remains unread. The summary provided here does not even begin to scratch the surface of the material. While this summary is based on more than a cursory review of the material, the fact is that any researcher will require weeks to effectively catalog and inventory the material, and months would be needed to actually read and digest the thousands of pages of documents. However, even in its present state the archive can be seen to consist of multiple groups of documents and materials that might best be described as follows:

A. The Clippings File

B. The Correspondence

-(1) The wartime and post-war personal correspondence between William Strand and his wife, Florence Strand;

-(2) The letters that Strand received from friends, family members, and colleagues during the war ; and

-(3) Correspondence and documents exchanged between Strand and The Chicago Tribune during the war.

C. Documentary Memorabilia

D. Military Memorabilia

A. The Clippings File

As noted, the archive contains more than 1,100 articles written by Strand as a reporter for The Chicago Tribune between 1938 and 1948. These articles reflect the rising career of an American journalist during some of the most important years of the nation, from the later years of the Great Depression, through the Second World War, and into the post-war period with all of its changes in politics and society. Strand’s first published articles for the Tribune, written in 1938, reported on performances by exotic dancer Sally Rand and on two murders in Chicago. Strand then wrote nearly 40 articles for the Tribune in 1939, these focusing on local politics, stories of human interest and, again, crime. Strand authored a number of pieces on a sensational murder-kidnapping case that no doubt captivated the Tribune’s readers.

By 1940, Strand was in Washington as a national political correspondent for the Tribune News Service, writing on subjects of national importance but still with the occasional venture back to crime stories. One article that Strand wrote in September of 1940 provided the Tribune’s readers with a glimpse into an ominous future: the United States Army, Strand reported, was in the process of conducting a product survey. The Army was attempting to determine just how many coffins were on hand in the United States.

1941 saw the formal entry of the United States into the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and Strand’s work in Washington the following year not surprisingly dealt with not only national political news but with matters of defense, economic and labor issues, and developments in the war itself. In 1943 the dateline on Strand’s articles changed, from “Washington, D.C.” to “Allied Headquarters, Algiers”. Strand had now embarked upon the next phase of his journalistic career, that of a war correspondent.

The articles that Strand wrote as a correspondent were often much like those written by his friend and colleague, Ernie Pyle. Strand authored pieces that focused not so much on grand strategies and major battles, but on the individual soldiers who were fighting the war. Just a sampling of some of Strand’s articles illustrates this fact:

– In October of 1943 Strand wrote a piece about an Army Air Force combat unit whose personnel were eating very, very well at their base in Italy, despite the usually less than appetizing nature of army rations. It happened, Strand reported, that one of the unit’s airplane engine mechanics had been discovered to have been a French immigrant to the United States prior to the war. He was a trained chef by profession, and he had worked at major restaurants and nightclubs in New York City. With the arrival of the war he had enlisted in the Army Air Forces and the United States Army, in its infinite wisdom, had then trained him to repair and maintain airplane engines. Now, however, he was preparing the meals for his squadron in Italy, and every morning another G.I. (who was the the son of Italian immigrant parents and who spoke Italian) would visit the local markets to purchase fresh products for the chef to use that day in preparing meals for the men.

– Strand wrote of the work of the Army’s front line surgeons and of G.I.’s playing baseball in the combat zones. In late 1943 he told his readers of the service of a particularly impressive combat unit in a piece that was headlined “Heroes Appear Among U.S. Japs on Italy Front.” Censorship regulations would have prevented Strand from identifying that unit with any particularity, but he was undoubtedly writing about the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Comprised almost entirely of Japanese American Nisei, it would become the most decorated American combat unit of the Second World War.

– Strand’s desire to tell the story of the average American soldier is compellingly reflected by a particular letter that Strand sent to his editor at the Tribune from Italy, found in an unusually thick envelope among the archive materials. A young American soldier, Alfred Ehrlich of New Jersey, had been serving as a combat infantryman in the 36th Division in Italy. In mid February of 1944 Ehrlich was wounded in action and, two days later, he died of his wounds. Strand had gotten to know the men in Ehrlich’s unit and, when they found that Ehrlich had been keeping a diary, they gave it to Strand. Strand transcribed the diary and sent the typewritten copy to his editor. Strand related that had made multiple attempts to craft excerpts from the diary into an article but that he had given up trying because the diary, in its entirety, was simply too compelling a document to be written about in a piecemeal manner. Strand told his editor that Ehrlich’s diary should be printed “as is”, noting that “It covers his whole fighting career, 41 days, from a replacement depot behind the lines to his death last winter in the hills before Cassino.” The diary, Strand thought, told the story of the American combat infantryman as no article that he wrote could ever do. Since any article publishing the diary would almost certainly have referred to Stand or carried his byline, and since no such article has been found within the archive, it appears that this diary remains unpublished to this date.

– Strand reported on the tenacious fighting around the ancient Italian abbey at Monte Cassino, and on a unique and feared Allied combat unit that was comprised of both Americans and Canadians. This was the legendary First Special Service Force. Many of Strand’s articles focused on soldiers from Chicago, or Illinois, or the mid-west, such as the story that he wrote about a B-17 bomber that had been given up for lost when it failed to return on time from a mission. The bomber, however, eventually appeared and landed, to the immense surprise of the squadron. The plane had been badly damaged on the bombing mission but it’s pilot, a lad from Chicago, had nursed the battered craft back through the skies at a distance of over 400 miles, returning the crew safely to their base.

– When Rome fell to the allies, Strand wrote of another American soldier, Sergeant John Vita, from New York City. The son of Italian immigrant parents, Vita had made his way to the very building in Rome from which Mussolini had harangued the crowds when he had ruled Italy from that city. Standing on the same balcony from which Mussolini had made his speeches, Sergeant Vita began addressing the people of Rome below him. In fluent Italian, Vita spoke of the great Italian people and of the need for them to overthrow the fascist government and to join the Allied cause. According to Strand, Sergeant Vita soon attracted a crowd that was larger and more enthusiastic than any that had ever heard “Il Duce” speaking from that same balcony. Vita told Strand that he had promised his parents back in New York that, if he ever had the chance, he intended to do exactly what he had done in exactly that spot. After all, as Vita firmly emphasized to Strand, HE was an American!

Interestingly, correspondence in the archive to Strand from the Tribune indicates that Strand’s newspaper was not entirely supportive of his focus on the personal stories of the war. In a message dated February 22, 1944, Strand’s editor made suggestions for stories and asked Strand to write more on strategy “and give less space to personal experiences stuff unless, of course, the latter is of the highest quality.”

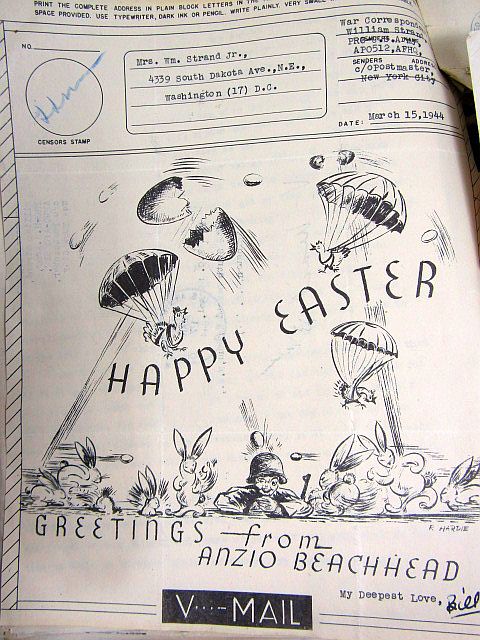

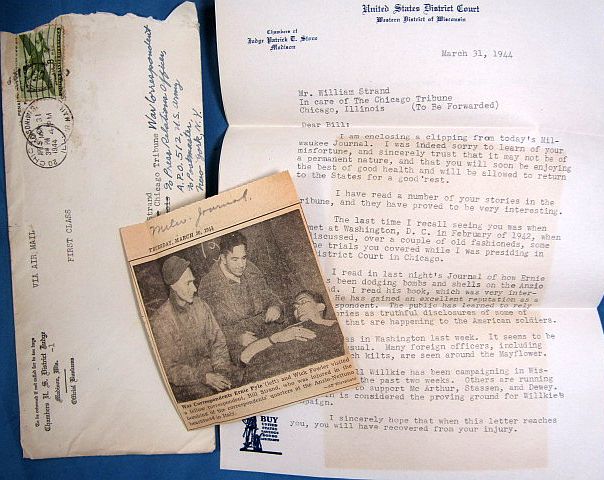

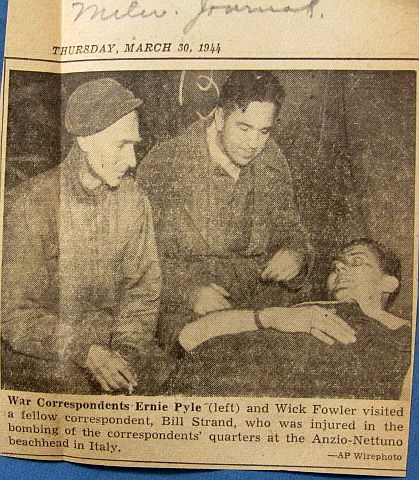

Strand himself made the news during the war. When the Allies invaded the Italian port city of Anzio, a protracted battle ensued that would see the American and British troops fighting for months to move off of the beachhead. A building in the combat area had been established as the press headquarters. It served not only as office space for the press but also as a residence for several journalists, including Strand and his friend, Ernie Pyle. One day the Germans conducted an air assault against the beachhead and a bomb struck the press building (which its residents had dubbed “Villa Virtue”). Strand, who was inside the building at the time of the attack, was wounded. Shortly thereafter a photograph went out over the wire services that showed the wounded Strand, lying in his hospital bed, with his friend Ernie Pyle sitting at his bedside. A clipping of the photo was sent to Strand in Europe by an old acquaintance, Judge Patrick Stone, who wrote to Strand on his letterhead of a United States District Court judge in Wisconsin. Strand and Judge Stone (who began his letter with the salutation of “Dear Bill”) had apparently met years earlier, when Strand was a crime reporter in Chicago and Stone had been in the city at the time. The archive includes not only the photo clipping and Judge Stone’s letter (which, like virtually every letter that is in the archive, is still within its original mailing envelope), but the archive also includes the cased Purple Heart decoration that Strand was awarded for the combat wound that he received in the bombing of “Villa Virtue” (one colleague wrote to Strand after hearing the news of the attack and said that he presumed that the press building would now be known as “Fallen Virtue”). For its part, Strand’s newspaper was obviously concerned about the well being of its correspondent. The archive contains a terse telegram received by Strand after his wounding: “CONGRATULATIONS YOUR ESCAPE STOP WIFE SENDS SYMPATHY STOP TAKE BETTER CARE STRAND HEREAFTER”, with the telegram signed simply “The Chicago Tribune”.

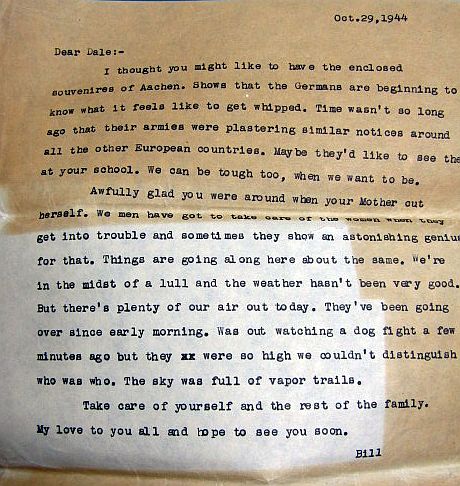

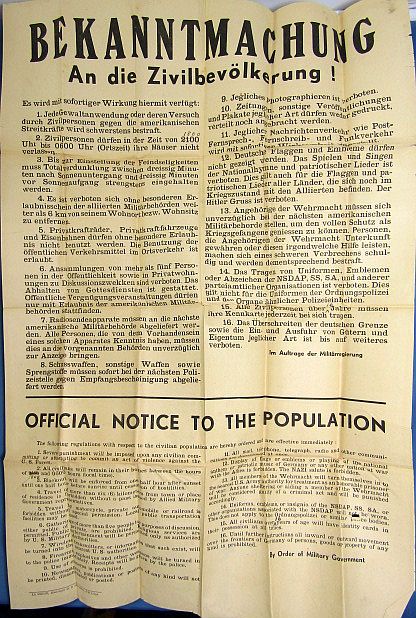

After having covered the war in Italy for many months, Strand returned to England, writing on British war brides and other subjects, before being placed with U.S. army units in western Europe following the D-Day invasion. He produced articles about the combat in Holland and he was a witness to the battle for Aachen, being present when it became the first city on German soil to be captured by the Allies. The American Army had had posters printed in France in anticipation of the victory. With text in both German and English, the posters informed the residents of the newly conquered city that they were now under the authority of the United States Army, and they were advised of new rules that were in effect, such as those which forbade the use of the Nazi salute or the wearing of the uniforms of the SS or the SA (the brown shirts, or “Storm Troops” of the Nazi Party). Strand acquired several of these posters from Aachen and sent them home to his son as souvenirs. They are present in the archive. He remained in that region when it became the site of the largest battle ever fought by the American Army: the Ardennes Offensive, popularly known as the Battle of the Bulge. Strand was a witness to the battle.

And then he quit.

The archive contains a letter that Strand wrote to his editor in December of 1944. Within that letter, which runs to several typed pages, Strand relates his frustration with the Tribune, or at least with one individual in particular. He notes that the war correspondents had been assured when they were given their overseas assignments that, every so often, they would return to the States for a “breather”. Strand by this point in time had been in the theater of combat operations for about 15 months straight. The letter recounts a number of issues that Strand saw with the paper and with his role as its war correspondent. Believing that these views, which he had expressed before, had simply been ignored, he announced his resignation. He stated that he would, of course, remain in the area of operations and continue to work until his replacement arrived. The letter apparently had its effect. Strand soon left western Europe for Iceland, from where he filed articles on the joint British and American wartime operations in that country. And then he was brought home to the United States for a “breather”.

B. The Correspondence

The Strand archive contains hundreds of separate letters running to thousands of pages. They can be roughly divided into four categories:

– The letters exchanged between Strand and his wife, Florence, during his time overseas as a war correspondent;

– The post-war correspondence between Strand and his wife, from 1946 and into 1950, including the period during which Strand was in Alaska;

– The letters that Strand received from friends, family members, and colleagues during his overseas service as a war correspondent; and

– The wartime letters and communications between Strand and his superiors and editors at the Chicago Tribune.

(1) The Personal Correspondence Between William and Florence Strand

The wartime correspondence between Strand and his wife Florence is contained within the archive, with Strand’s wife having assembled her own letters to her husband in chronological order in a binder, a suggestion that Strand had made to his wife in one of his early letters to her. His letters, almost always beginning “Dearest One”, commence with his arrival overseas and they continue through his service in wartime Europe. Sometimes he also sent Florence copies of letters that he had sent to his editor at the Tribune. As to the correspondence from Florence to her husband, the original letters are not present because Strand no doubt knew that his wife was making and keeping copies of every one of her letters to him. Indeed, she even numbered her letters to her husband. Her first letter was written on September 26, 1943. Her correspondence ended for a period with “Letter #97”, written on December 26, 1944. It seems that it was not too long after letter 97 that Strand arrived back in the United States for his “breather”. Florence apparently resumed her correspondence when her husband returned to assignments at a distance, writing him more letters between April and July of 1945 (a letter dated May 13 of 1945 was in fact titled “No. 1 of Series 2” by Florence, but it appears that she did not maintain the numbering of her later wartime letters). This voluminous correspondence between a husband on the front lines and his wife on the home front, comprised of hundreds of lengthy and legible, typewritten letters, is a window onto the Second World War that is likely as unique as it is extensive. The materials are made even more compelling by the fact that both of the writers who were involved in this exchange of letters were very intelligent, observant, witty, and clearly conscious of the importance of the times in which they were living.

(2) Friends and Family Correspondence

There are over 200 pieces of correspondence that Strand received during the war from friends and family members. This portion of the archive includes a letter that Strand wrote in which he provided a graphic description of the battle for Rome in June of 1944. However, it must be noted that any examination of this portion of the archive will present something of a challenge to the researcher, because over 100 pieces of the correspondence are World War II “V-Mail”. The “V-Mail” system was developed to enable planes and ships to carry a greater amount of wartime correspondence by maximizing the available space on transports and the fuel that was required to move the material. This was done by reducing the physical size of the letters themselves. “V-Mail” correspondence required the writer of the letter to place their correspondence on a single sheet of paper. This piece of paper was then photographed and the resulting photo was reduced in size, folded once, and placed into a special envelope that was much smaller and lighter in weight then conventional letter envelopes. It appears that much of the “V-Mail” that Strand received came from his mother. Those letters were typed, single spaced, and seem to have always taken up the entire page. As such, in their reduced size, they will likely require any researcher over 40 years of age to use a magnifying glass to read them. An additional complication with the “V-Mail” material arises from the fact that Strand made it a point to keep every piece of correspondence in the envelope in which it had arrived. It seems that the flaps on the V-Mail envelopes must have been made with a particularly effective sealant, such that Strand replaced the letters in their envelopes and, with the passage of time, those envelopes are now once again sealed just as tightly as they were on the day that they were mailed. The only alternative explanation for this situation is that, over a period of many months, Strand received dozens of pieces of “V-Mail” correspondence (with most, it seems, coming from his mother), and then, for reasons unknown, Strand never opened them.

(3) The Strand-Tribune Materials

In the Strand archive there are letters, cables, and other documentary materials relating to the work that Strand was performing as a war correspondent. These consist of communications from the Chicago Tribune about Strand’s work, sometimes with suggestions for subjects of future articles. The materials also include receipts for expenses of various sorts that Strand incurred, as well as additional documents relating to his expense account as a war correspondent. The Tribune was certainly paying attention to the costs. Some of the receipts reflect the fact that, while he had been in London, Strand had stayed at the Savoy Hotel. In July of 1944, Strand’s editor wrote to him and said “I ask you to keep your expense account down….For instance, I don’t think it is necessary for you to live at the Savoy.” Yet Strand’s editor was obviously pleased with the work of his correspondent. In a telegram of November, 1943, Strand’s editor wrote “PLANES MULES EXCELLENT STOP [undoubtedly referring to one of Strand’s recent articles] CONTINUE TIGHT WRITING STOP”. These materials also include correspondence to Strand from fellow war correspondents as well as notes made by Strand himself (which were, like everything else, typed). One such page of notes is titled simply “Things to Remember”, and it contains numerous statements, most of a single sentence, describing things that Strand had seen and that he obviously wanted to keep in mind for future articles.

C. Documentary Memorabilia

Throughout the Strand archive are found various documents that Strand kept as personal souvenirs. Reference has already been made to the posters that were created by the army for use in the German city of Aachen. Other examples of such materials that have been found include the following items:

– A small map of Rome. Attached to the map with a paper clip is a typed note from Strand, identifying it as a map that was distributed to war correspondents when the American Army captured and entered Rome.

– The program for a presentation in the Royal Opera House in Rome of the Irving Berlin musical “This is the Army”. A typed note from Strand inside the cover recounts that Irving Berlin himself attended that performance and, after the last curtain had fallen, he appeared on stage and addressed the audience. He told them of a memory that he had: that as a boy growing up on New York City’s East Side, he had heard the Italian immigrants singing the song “Oi Marie” [“Oh, Marie”]. According to Strand’s note, “He asked the white-tied and bejeweled Romans to sing it for him again. They responded in notes that twisted your heart. It was a moment to remember.”

– A newspaper article that was published during the battle at Anzio (and not written by Strand) describes a propaganda leaflet that the Germans were dropping on allied troops in an attempt to sow discord in the alliance. Each side of the leaflet featured an American political cartoon from before Pearl Harbor, and each of those cartoons depicted Josef Stalin as a despot and a murderer. One of those cartoons had appeared in a 1941 edition of the Chicago Tribune, and a reproduction of the newspaper’s masthead appeared on the leaflet above the cartoon. Strand sent this newspaper article home and, with the article, he sent home one of the actual propaganda leaflets, which he had obtained at the Anzio beachhead where they were being dropped by the Germans.

– An Italian picture postcard of a Villa on the sea carries a typed note with it which reads “This isn’t far from the spot where I got my Purple Heart”.

– A sheet of white paper on which, written in pencil, are two columns of numbers. One column is headed “Bill” and the other is headed “Me”. A typed note from Strand identifies the document as a score sheet from a game of Gin Rummy that he had played with fellow correspondent Ernie Pyle and during which Pyle had kept the score. Strand noted that all of the handwriting on the sheet was Pyle’s.

There may well be more such pieces of documentary memorabilia within the archive. Some of the items described above were only found by happenstance, during a review that was conducted for the purpose of preparing this summary. During that review the contents of some envelopes were examined, almost at random, revealing that they contained more than simply letters.

D. Military Memorabilia

The documentary archive has with it 34 pieces of World War II military memorabilia. These items consist of a number of different pieces of military insignia that were worn by Strand, to include 25 examples of quite rare “War Correspondent” insignia, most of them being British made. The other military insignia worn by Strand includes a British-made example of the U.S. Army shoulder patch that was worn by an individual assigned to Allied Supreme Headquarters in London; and there is a shoulder patch for the U.S. 5th Army, the organization that had engaged the Germans in Italy. Also present is Strand’s cased Purple Heart decoration and a cloth bag, on each side of which is the large word “PRESS”, presumably used by Strand at times to carry or send articles. Finally, there is a small U.S. Army bandage tin. The medical dressing that it originally contained is now gone, replaced by shards of shrapnel and bits of glass, and it also contains a typed note from Strand explaining the circumstances under which the tin came to be opened and the bandage extracted, and explaining as well the significance of the metal and glass that are now in the container.

III. Conclusion

The thousands of documents in Strand archive comprise an extraordinary historical record of the life and work of an American journalist and war correspondent. It is almost certainly unique as a historical group.

Sold!